If you’ve played with or built AR apps,

05/03/2013 Leave a comment

If you’ve played with or built AR apps, you might find this UX article interesting as applied to augmented reality. http://ow.ly/kHhui

05/03/2013 Leave a comment

If you’ve played with or built AR apps, you might find this UX article interesting as applied to augmented reality. http://ow.ly/kHhui

03/29/2013 Leave a comment

MediaPost’s Search Insider has a nice rebuttal argument (linked below) to our recently commented eBay study claiming that paid search has a negative ROI for branded search terms, and a low ROI for outlier search terms. The 3 point rebuttal?

I think the first two points are fluff, but the third shows that maybe eBay’s study was just a bit premature. The best test will be to see whether eBay actually pauses its paid search expenditures in support of their own study findings.

Anyone inside eBay willing to comment??

03/26/2013 Leave a comment

We’ve been talking to various investors in the Los Angeles area for quite some time now. There are a host of funding options – just like in Silicon Valley – ranging from:

And really, that’s it. What becomes apparent is that the real funding sources for early startups – the sources that provide not only liquid capital but also valuable opportunities, strategic partnerships, experience leading to scalability and/or exits – are in the vast minority. Add to this the fact that these real funding sources are not appropriate at every stage of a startup’s growth (i.e. very rarely would a company approach an accelerator after having participated in an incubator), and the entrepreneur has a very narrow path to access outside investment.

So what’s missing? Well, first, you’ll note I don’t use the term “unicorn” anywhere. Those are always best left to small girls’ tshirts, and the hipsters who try to wear them ironically.

Second, unlike Silicon Valley, there are not any institutional-sized service providers willing to bet their startup-level services on equity in a company (i.e. Wilson Sonsini). Service providers in LA are notoriously un-venture minded.

Third, unlike Silicon Valley, there are very few active angels who have experience in tech startups. The ones that ARE here in SoCal are so over-burdened with approaches, that meeting with them is like booking an appointment with a Fortune 500 CEO, involving gatekeepers, referrals, schedule conflicts, and sometimes travel.

Fourth, unlike Silicon Valley, SoCal’s investment community is notoriously “traction dependent” – requiring that a startup have an existing community of users and much deeper proof of concept before investing. While this also happens in Silicon Valley because the cost of starting a company has plummeted so dramatically in the last 10 years, the investment community in SoCal does not have a good track record of being able to “pick winners” based on back-of-napkin conversations. Perhaps this is due to the fickleness of the movie industry in LA – you can have a great script, great cast, great director, huge budget – and still end up with a bomb that won’t sell to an audience. It seems like the investment community in LA tries too hard to de-risk the tech startup scene on objective measures because they’re worried about the subjective plot elements of a startup – “will it resonate with an audience and be marketable?” – rather than the Silicon Valley perspective of “will it solve an identifiable problem or provide a new process?” Innovation takes second seat in LA compared to marketing.

Previously, as an entertainment attorney in Hollywood, I would often create a metaphor for writer/director/producer clients about film investment and investors. I would say “Everybody, regardless of their film industry experience, has a little film reel running through their minds when they read a script – investors included – and everybody envisions a different version of your film. When the director comes along and spins up a better description of what he/she is going to put on film, the investors’ visions change somewhat, but still are not going to match the director’s vision. It’s only when the investors start seeing the dailies (the daily rough film sequences) that they start to see where the real vision is headed. And then investors want to be the directors and make their own version of the film that they originally saw in their heads.”

This last point seems to be one of the key differences in the investor pool in SoCal. Investors here really need to be shown that semi-final working vision before they’re willing to commit capital. They want to see the dailies. They don’t have the technical skill or experience to visualize the project in its early stages, whereas more angel investors in Silicon Valley actually come from the tech world, and can envision a project based on early descriptions and technical achievements. This investor class – the Black Stallions – are really what’s missing here. Typically, they tend to get packaged into an accelerator program in town, and bundled as part of the investment package that’s sold to entrepreneurs. So these Stallions are turned into Cattle Herders, and end up spending their valuable social capital on projects that aren’t going to be ground-breaking or disruptive social innovations, but that are optimized to (or resort to) provide a comfortable 2-10x return.

If Silicon Beach wants to be more like Silicon Valley, the angels here have to learn to run with the horses.

03/14/2013 Leave a comment

A new article by Mark Sweney from The Guardian (UK) summarizes an eBay study – where eBay evaluated the incremental traffic generated by paid search (paying for an ad to be associated with a search term, like via Google AdWords). If they were using the title of their study to measure search effectiveness, then it’s no wonder they didn’t find any results – it’s a search-bewildering mouthful (Consumer Heterogeneity and Paid Search Effectiveness: A Large Scale Field Experiment). But despite its unwieldy title, the report effectively draws direct fire on Google’s previous self-supportive studies that claim Paid Search results in higher overall clicks, even on organic search results (that there are more clicks on the organic search results in the presence of paid search, than there are on organic search results in the absence of paid search). In the eBay study, they turned off paid search on Bing and Yahoo, while continuing Google AdWords paid search, and then evaluated the resultant traffic flow all the way through to completion of purchase.

eBay’s conclusion? In regard to branded search terms – “AT&T”, “Macy”, “Safeway”, “Ford”, “Amazon”, etc. – a minority of the spend on paid search yields some new customers which are ROI positive, but the majority of paid search spending results in clicks by existing or even long-term customers, which means the ROI on such ad spending is actually (hugely) negative. Think about it – when you use Google to most easily and directly find a specific website like Amazon.com, do you automatically click the highest-up link, maybe even in the yellow “sponsored” section of search results? That action right there is what eBay is referring to. People use the Google search bar as a lazy method of finding a known website (i.e. eBay), and they just click the highest link for the URL they’re looking for (eBay.com), even when it’s in the paid search section – which costs eBay money paid to Google. That “searching” customer was going to eBay anyway, they were just using the search bar as a proxy to typing the long-form URL. eBay concludes that paid search is ROI negative – so let’s see if 1) they stop using paid search, or 2) they continue spending on it as a purely defensive move to prevent other marketers from taking the top search slot and possibly siphoning off otherwise “organic” traffic.

Conclusion 2 (ours): This negative ROI result is amplified by Chrome and other web browsers that use the URL bar as a default search bar – allowing users to just type “eBay” instead of ebay.com, which drops the user into Google’s search results for “eBay” not http://www.eBay.com, where that user is likely to just click the highest occurring link to ebay.com, which is a paid search slot. I think about this every time I conduct a search, because I’ve run paid search campaigns before, and have become very cost-conscious about search as a result – and that’s from spending maybe a few hundred dollars, not a few millions.

Conclusion 3 (ours again): the eBay study reveals that eBay regularly runs paid search campaigns, using over 170 MILLION search terms, in an automated system that adjusts the keyword terms daily. Now, maybe you’re a SEM pro already and that number doesn’t shock you. But if you’re an online or local business trying to find web traffic through SEO or SEM, then you had better be using an automated system like Marin to compete with the larger online companies. 170 MILLION KEYWORD TERMS!!!! Think about that number before building any business models around SEM competitiveness.

03/07/2013 Leave a comment

“Product-Market Fit” is the idea that a company needs to 1) create a product that 2) fits a need in the market – a need that is 3) poignant and sustainable enough to generate continued interest by customers, and 4) thereby generate revenues (or other benefits) for the company. By relying on the term “market” in this definition, we necessarily must start with the concept that a market pre-exists; that a market can be identified a priori; that a market’s needs can be assessed and addressed.

What if you’re developing a product that is leading a market? What if you’re creating a market? How does a responsible company/product owner evaluate whether their efforts are worthwhile or headed in the right direction?

Welcome to our world at Holofy. We’re creating a new digital ad product that will supplement existing advertising out in the world. This combination of digital and physical takes place via augmented reality and, to our knowledge, is the first of its kind. The goal is to make advertising better – less sucky, less prevalent, more relevant, and more engaging/engage-able. Right now, this engagement is via the screens on smartphones. Holding up your phone like it’s a video camera to engage with the world through the viewscreen has become easier for people over the past 2 years, but it’s still not the most natural way of using a smartphone. So our solution is actually aimed at the moment in the market when Google Glass and its progeny are more ubiquitous display tools (here’s everything we know about Glass). Granted, we don’t know when that will occur. We also don’t know if smartglasses will be widely popular. But we subscribe to the idea that we don’t try to predict the future – we try to build the one we would want to see happen. And we do know that we want to see a world with better advertising than what we currently experience – current advertising sucks. Building the future is active, not passive. So we’re actively building a solution for a future market that doesn’t exist yet – which often makes for difficult conversations with investors who perhaps aren’t as forward-minded in this space as we are.

What are the steps involved in evaluating whether we’re developing a product that the market may want or need in the future, when the market isn’t currently mature enough to express such needs? We think it’s these 10 points:

revenue sources and/or products. You are not creating a direct line of product development towards the future product like stops on a subway. You are creating a river delta where the future market is the sea, and the building blocks are the rivulets branching outwards towards it. Prioritize building blocks and derivative products that are themselves strategically supportive of the new proposed product. Prioritize blocks/products that strategically support 1) customer development, 2) revenues, then 3) corporate brand-building & marketing.

revenue sources and/or products. You are not creating a direct line of product development towards the future product like stops on a subway. You are creating a river delta where the future market is the sea, and the building blocks are the rivulets branching outwards towards it. Prioritize building blocks and derivative products that are themselves strategically supportive of the new proposed product. Prioritize blocks/products that strategically support 1) customer development, 2) revenues, then 3) corporate brand-building & marketing.So then, this leaves us at Holofy to evaluate our own 10-step process.

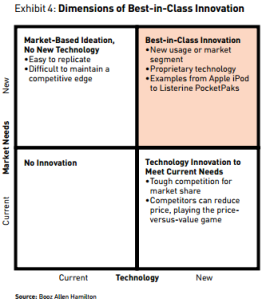

We’re aiming here, at the upper right quadrant:

So there you have it – our thoughts on innovating a new product/market category. Stay tuned to see how we execute on this outline. We’re Holofy, and we make ads better.

03/01/2013 1 Comment

“Advertising” as an industry basically sucks.

Sure, there are parts of it that are romantic – creating an amazing ad campaign that resonates with people on a human level (see TED’s Ads Worth Spreading). Some of those ads are “stories” that truly enrich the audience’s world view – they’re not directly about products or services necessarily, but the cross-roads between the audience’s lives and a product/service, perhaps.

But for the most part, advertising involves hawking things at people in the hopes that they’ll buy. Buying and selling fuels our economy – Half the world is selling, half the world is buying (unless we’re talking about food, and then apparently half is just thrown away).

As everyone knows, the psychology of the consumer is the real engine behind a capitalist society: The psychology of the stock markets determines whether a stock goes up or down, not the fundamentals of the company behind the stock; The psychology of the househunter determines whether she will pay more or less than the asking price from the seller, not really the true underlying value of the wood, metal and sheetrock composing the house. What the banks and policymakers are constantly searching for is “irrational exuberance”

So consumer advertising is aimed at the psychology of the consumer – creating desires & plying aspirations, playing on fears of exclusion or loss, breeding competitiveness… Advertising is illusion – “aspire to this lifestyle, and buy this product to then be included in this lifestyle group.” The link immediately above highlights that Lehman Brothers was “responsible” in the shift from functional advertising (promoting features & solutions) to desire-based advertising (think of any ad where you don’t see features of the product, but see some aspect of lifestyle however remotely associated with the brand/product). We’ve now shifted into entertainment advertising – advertainment – where the goal is first “Attention Share” of their audience, and then a lifestyle link.

There’s no doubt that sometimes advertising can be helpful – it might bring to light a product or even a whole category that the audience didn’t know about before. But more often, advertising these days is just “top of mind” advertising, designed to make one product or brand the first thing that a shopper thinks about when in fact they do leave the house to shop for something.

We’re trying to upend that advertising model. It’s difficult however. If your mind is the type to lean towards conspiracy theories, you can look at James Glattfelder’s TED talk where he revealed his team’s research into control of financial markets – the same corporation/group that caused the shift into desire-based promotions is also in control of the financial resources of the world markets.

Our goal at Holofy is not to create more advertising. God – enough with advertising already. Holofy’s goal is to help make advertising less sucky – to make it more useful, and about helping people find the things they need, not highlight things they desire or should have. So the extent that existing advertising can grab attention – it’s being designed to, afterall – then we can leverage that attention to give our audience better information about those products, more local resources to find something, better comparisons and alternative products to what’s being pushed in front of their faces in the underlying ads. Check out what we’re doing and support: HOLOFY.

12/11/2012 Leave a comment

This episode can be found at both www.untether.tv and at www.thelbma.com

Show highlights:

1. Summary of The LBMA augmented reality event in New York (1:15) – In case you don’t know it folks, augmented reality is going to blow your mind. The LBMA hosted a panel discussing how Blippar and GoldRun are currently ramping up to that.

2. Where’s My Wife? Saudi government tracking wives (7:00) – Creepy app that (somehow) tells Saudi men when or if their women have left the country. Like, if they’re fleeing the abuse and heading to a country where they can hold an actual conversation.

3. Launch of Joingo targeting platform (12:15) – A geofencing platform that allows SMB’s to select geographical areas to market to. Apparently nothing original here other than an iteration that links the platform to SMB CRM software.

4. Almax mannequins track shoppers in stores (15:50) – Italians using mannequins to watch your every move in stores and extrapolate shopping data from what they “si”

5. FedEx launches mobile/location holiday campaign (22:10) – with IMDB? Looks like Hollywood/Amazon just got a quick sugardaddy in FedEx’s nonsensical app.

6. Is this the beginning of the end of group buying? (25:00) – OK, these guys hate Groupon and grouponclones. Schadenfreude galore over recent layoffs at Living Social.

Featured Guest

Terry Blake, head of business development EMEA for Lemon Mobile. (31:25) – LEMON stands for “Location Enhanced Mobile Opt-In Network”, and they’re doing geofenced opti-in loyalty messaging for discreet fan bases, like say, the NY Jets fans. Interesting point – Jets franchise is trying to find ways to limit tailgating at the games, so they can encourage more people to head to the concessions and merchandising stands.

Funding / M&A News

1. NCR acquires Retalix for $650M (41:20)

2. Google buys IncentiveTargeting (44:10)

3. AdNear raises $6.3M (47:10)

10/22/2012 1 Comment

We’re going to discuss real estate and films and technology in this post, so don’t get scared by our opening section on real estate – there’s a point that is very technology, and yes, comics, related.

There’s something new happening in the world of real estate… new land is being formed even as we type, right in front of our eyes. This new land is not made of rock – it’s digital. No, we’re not talking about World of Warcraft or some other gaming system with purple trees and elves with swords. We’re talking about a digital technology that is changing – augmenting – reality as we see it, real estate as we experience it, and real property as we define it. This “Augmented Reality” technology is a live camera view (most often via your smartphone camera) of a physical, real-world environment whose video elements are augmented by the camera’s computer – basically, the computer understands what your video camera is looking at and can add digital information or graphics into the video scene in real time, adjusting the pose, perspective, and even lighting to make these new elements look like they are a part of the native environment. The computer augments reality.

As others have started to report, (mashable) (2) (3) (4), Augmented Reality is beginning to be super-imposed on real estate (billboards, building fronts, etc.), resulting in a burgeoning area of law – virtual air rights – to complement an existing area of computer law – virtual property rights. Virtual Property Rights relate to ownership and control over virtual property – electronic intellectual property (ideas, information, plans, pictures, etc.) residing on computers. However, Virtual Air Rights are different and are an extension of physical property into virtual space.

As background, in traditional (real world) property law, physical property can have “air rights” above and around that property – the exclusive right to use that physical air space for certain purposes. This is most typically represented in an air-rights lease, where a land owner leases the air space above his land to a building developer. The developer erects an office building or other commercial space into the airspace over the land (up to a given height as provided in the lease), and the lease in turn gives him the exclusive right to use the ground underneath the airspace and the new building. The exclusive rights to the air space over the land often extend to the limits of space, but can sometimes be limited to a fixed altitude, depending on the desires of the land owner, permit regulations, or other externalities. A successful air rights lease is able to coordinate or avoid these external forces, often through complicated and expensive political means. Thus, an exclusive air-rights lease is a valuable property right in and of itself, and is an important bankable asset to a building developer. Principally speaking, “property” derives much of its value from the right to exclude other people from it. Those property rights – air rights included – are less valuable when they are not exclusive.

Additionally, our society has seen an explosion of external building facade leases – a building owner will lease the exterior surface of his building to an advertising company for the installation of supergraphic advertisements (billboard advertisements the size of the building wall). These leases, too, can be a very valuable asset, with supergraphic ad rates running more than $100,000 per month (a particularly well-positioned building in Los Angeles, for example, has been known to earn $350,000 per month for supergraphics on its walls). The rates are dependent upon i) the volume of traffic near the wall (i.e. potential audience), ii) the desirability of the demographics of the surrounding area and resultant traffic, iii) the “viewability” of the wall (is it in a good line of sight, elevated, or otherwise blocked from the traffic’s view), iv) the availability of other advertising options in the area, and v) the number of other distracting supergraphics on other nearby buildings. Supply and demand definitely play a part in the pricing of these ads, but again, exclusivity is also important for setting those prices (how much would an advertiser pay if the wall were layered in different ads, making the whole wall essentially unreadable?).

Virtual Air Rights (VAR’s) come into play when there’s a new “virtual” or digital use of a physical air space. How should we evaluate these virtual air rights? Can a property owner enforce exclusive control over all virtual space around his property? Let’s pull that question – and the underlying technology – apart. When someone creates a virtual space (i.e. a website or other digital recreation of real space), they have in effect created a whole new landscape. And they can do this an infinite number of times, even if using real space as an anchor spot for their digital creation. All they have to do is make a new “layer” which exists simultaneously with all the other “layers” of virtual space. Suppose we have a programmer creating a virtual space. Programmer #1 can certainly put access restrictions in place to exclude people from Virtual Space #1 – but those excluded people can also make their own digital layers as Virtual Spaces #2, 3, 4, 5… ad infinitum, if they so choose, which exist simultaneously with Virtual Space #1, without interfering with Space #1 or the underlying physical space. This non-interference could be the lynchpin for legal determinations on the subject when a testable case arises.

Testable virtual space scenarios do exist, such as when someone takes a picture of a real world billboard, puts that picture online, uses computer software to alter the billboard’s image, and superimposes a new ad on the billboard but leaves the rest of the image untouched. This isn’t far fetched – Google has filed this very patent for its Street View mapping display system. When Google’s photographic cars drive the streets of the US, they capture everything on camera, and then use those images to recreate an eye-level view of the world on your computer. Because the Google cars aren’t driving every street every day, their online images get older and older over time – so what you’re seeing in Google Street View is actually the world as it existed 6, 12, or maybe even more than 24 months ago. The Street View cameras also capture billboard ads in situ as the Google car drove by. The streets, buildings, and building facades change much less frequently than those billboard ads, so now Google has created a system to replace those billboard ads in Street View with newer ads – effectively superimposing new ads on top of the real life images of the billboards. Google has spent considerable time and money recreating this new virtual space, which is a useful tool for anyone looking for directions into a new part of town and would like visual cues of what a particular address looks like. Google can then certainly regulate i) who gets access to this Street View information, and ii) who gets to overlay a new ad on an old billboard – Google can exclude advertisers who don’t pay them for this right because there are additional costs involved in doing so and Google holds the keys to this new territory. But pointedly, there is nothing to stop someone else from coming up with the same result using a different method. (In this scenario, patent laws will protect Google’s method – and its virtual space layer – from competitors. So it is intellectual property law more than traditional property law that will rule this virtual space.)

Will this method of “virtual advertising updates” create any problems for Google? Since they have not implemented this system yet (at least not in a wide public roll-out), we haven’t seen any lawsuits regarding this practice, so it remains to be seen whether billboard owners will take umbrage with this practice, or be able to successfully litigate any cases on their merits. It’s hard to ever imagine CBS Outdoor rolling over and allowing Google to overlay CBS’s billboard with new ads that CBS didn’t sell. Thus the clash of old world property (CBS Outdoor) and new world virtual property (Google) arises anew in the advertising space.

Courts around the country have only just begun issuing determinations on property rights existing in virtual space. Most on point to the Google discussion above is a case where real-life Times Square billboards (sponsored by Samsung) appearing in Sony Pictures’ “Spiderman” movie were digitally altered in the movie to contain advertisements from brands other than Samsung and friendly to Sony. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals (New York) ruled that there was no violation of any property rights, trademark rights, or tradedress rights – denying all of the claims of the billboard owners and Samsung. (Sherwood 48 Associates v. Sony Corp. of America, 213 F. Supp. 2d 376 – Dist. Court, SD New York 2002) The ruling held that because movies are fictional, the filmmakers are allowed certain creative license in depicting the world as they’d like to see it – free speech in action, and a fairly settled area of law. But in the area of virtual property law, the court held that the new superimposed images in the movie did nothing to interfere with the real world billboard operations. The alterations existed solely in the movie and in virtual space, and had no functional impact on the real billboards.

Meanwhile on the West Coast a year later, the California Supreme Court weighed in on how an email, critical of Intel and sent over Intel’s internal email system, does not interfere with Intel’s physical property rights in its email system.

Such an electronic communication does not constitute an actionable trespass to personal property, i.e., the computer system, because it does not interfere with the possessor’s use or possession of, or any other legally protected interest in, the personal property itself… Intel’s claim fails not because e-mail transmitted through the Internet enjoys unique immunity, but because the tort of trespass to chattels—unlike the causes of action just mentioned—may not, in California, be proved without evidence of an injury to the plaintiffs personal property or legal interest therein. (Intel Corp. v. Hamidi, 71 P. 3d 296, Cal. Supreme Court 2003)

This means that an electronic usage of a real world system does not damage that real world system merely because the electronic usage is associated with the real world system – there has to be some real damage perpetrated by the electronic usage (i.e. a computer virus damaging the system, an electronic libel issue damaging a person or entity associated with the system, or maybe a denial of service attack depriving the owner of use of the system). Just because an electronic use exists in relation to real world property does not automatically equate to a trespass to that property.

So it appears that initial court rulings have sided against claims of damages when a digital version of a real world space contains a new look or feel. After all – what was damaged? The physical space continues to be used the same way it was intended to be used, by the same parties. When someone like Google takes the trouble of creating a virtual world, they have effectively created a new usable landscape that is accessible only through their digital gates. No real space has been harmed in the making of their space – but like a digital volcano, they’ve created a new usable layer and doubled the usable space out there. So when a user of Google’s services steps through their digital gate, that user is essentially stating that they are willing to experience Google’s view of the world. Even if Google’s experience includes new ads, or new versions of a building’s exterior, or new buildings entirely, that doesn’t affect the real world or our use of real world articles or property. If Google has created a valuable experience, then more people will opt-in to that experience. If it’s not valuable, or if it’s damaging, then people will stop visiting. It’s a plain market-forces situation, probably not a legal one, that will determine if Google’s view of the world will continue. The real world continues on, just as before, but now Google’s users would be stating that they are voluntarily looking at the world with different eyes. How will property owners try to enforce their rights against a willing public that is simply viewing the world differently, and not damaging anything in the real world?

Is this appropriate? Would it be more appropriate for a property owner to also be able to exclusively lease off these Virtual Air Right’s? It sounds attractive (to property owners) but it also sounds like a logistical nightmare.

So how would we encourage the creation of VAR’s? Or should we encourage it at all? While Google has patented its billboard replacement system, it has also been working on Google Glass – a set of eyeglasses that are powered by your smartphone and which display alternative information on top of the world you’re looking at through them. It doesn’t take much leap of the imagination to envision a time when so many people have opted in to Google’s vision of a billboard that they are no longer paying attention to, or engaging with, the real world billboard, potentially resulting in real economic loss to the billboard owner. Is this a bad thing? After all, the public had very little to do with the erection of that real world billboard in the first place. And ever since that billboard was put up, it began broadcasting its marketing messages to the public without their approval or opt-in – you can’t choose to unsee a billboard once you’ve driven past it, and you can’t participate in any of the decisions about which ad should go up on it. So the billboard owners were actually imposing their marketing messages on the public’s eye in the first place – is it a bad thing if the public chooses a way to see the world that doesn’t include that billboard owner’s particular message? What if there is a higher and better use of a billboard’s physical presence? What if there were a way to augment that billboard so that it provides better information, more relevant information, or more publicly-minded information? What if there were a way to make billboards disappear if you didn’t want to view them at all? Shouldn’t we want to encourage the creation of such a system and not wait for when – or if – the billboard owner decided to build something similar?

This kind of scenario now begins to bring into question commercial impact of augmented reality layers. As attorney and AR enthusiast Brian Wassom previously commented, AR’s “use in commerce” is also a new and developing area of law and society and worth exploring deeper – AR layers have the specific potential to use trademarks as data layer markers, and then those data layers (will likely) distract users from the underlying trademark or ad. It’s doubtful that a company will be allowed to use its competitors’ ads as triggers for information on its competing products – but what if they are simply categorical matches, instead of directly competing product matches? A categorical match expands the consumer’s options, instead of confusing them in regards to a specific product. Where does use of AR “in commerce” become too close to a trademark infringement?

Augmented Reality technology is making all of this happen right now. It can take the fantasy of the Spiderman movie and put it squarely on top of the real view of the world. It takes the layers of information created everyday on the internet, and brings those layers to the world around you. Is this a trespass, to superimpose information and graphics onto the real world? Is this a confusingly competitive use of the underlying object or image? Or is this a higher and better use of the real world, using real world locations and property as anchor-points for more and better information?

ABOUT HOLOFY

We at Holofy are doing what we can to create such a system that improves how billboards in particular, and printed advertisements in general, are seen and engaged with by the public. Holofy is a system that layers any print ad anywhere with A) information about hyperlocal businesses selling those products, B) information about associated groupons or local deals on similar products, and C) hyperlinks to the webpages of the underlying ads themselves (if anyone ever wants that). Our goal is to make all the ads already out there in the world – better. And make people aware that they can – and should – expect more from the world around them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.